Team 11 – Margot Gersing, Eliza Pratt, Thomas Youn

Background

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus and the nation-wide lockdown and self-imposed quarantine that followed, caused disruptions in all aspects of our lives. As we huddle around ourselves in our own homes, the distinction between communal and personal space has been blurred. It isn’t difficult to make a connection between the rise in divorce rates and domestic violence and the fact that we are being forced to live in the same space at all times. The need to respect each others’ space, both in communal and private settings, has never been more important.

Our Focus

For our intervention, we decided to tackle the seemingly insignificant behavior, but one that we saw greater potential to make positive change in our households. We looked at the way we used our water glass; how often we use new glasses, how we neglect used glasses, and how these glasses slowly invaded our living spaces.

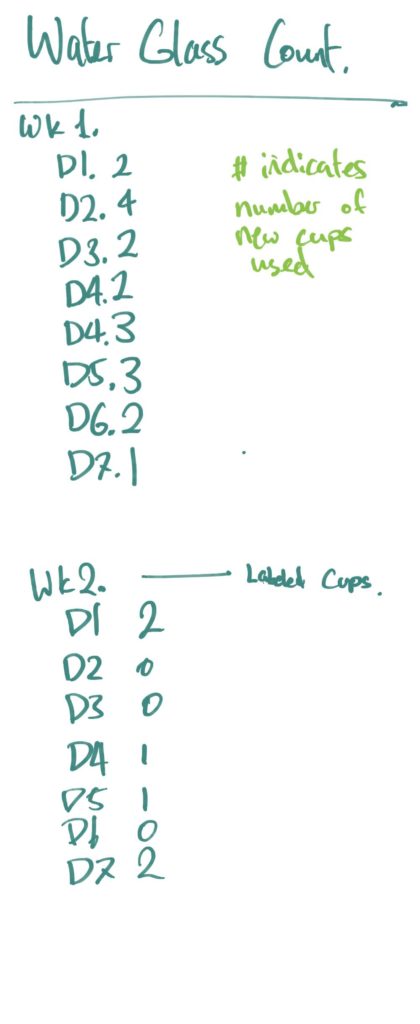

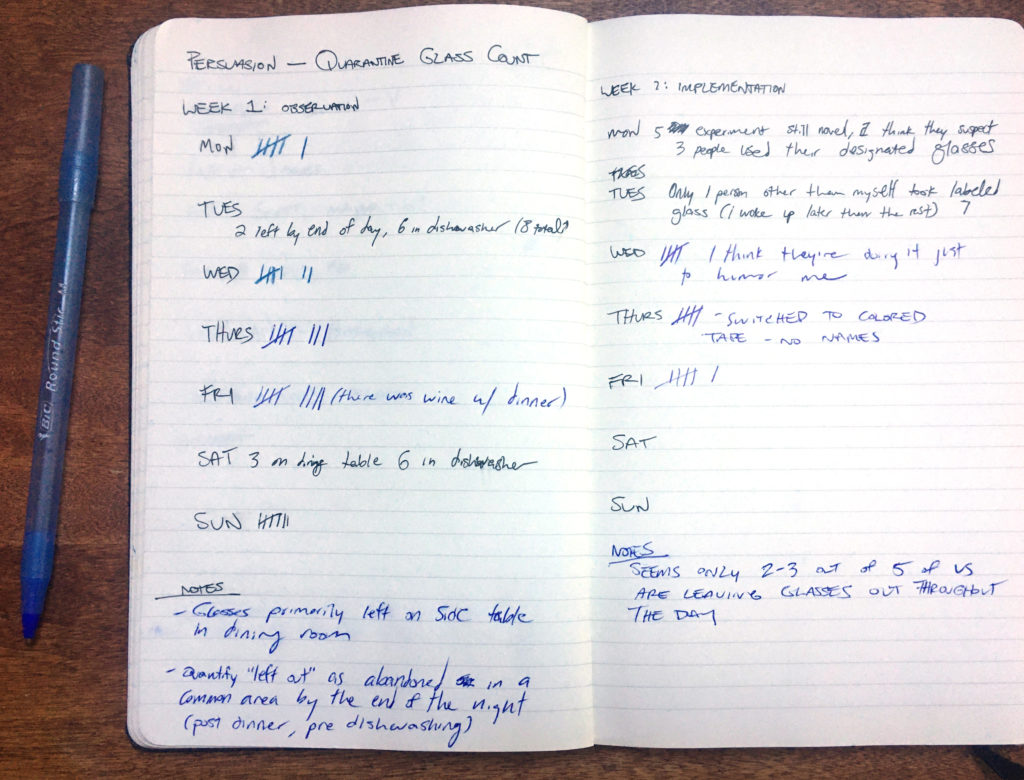

Initial Observations

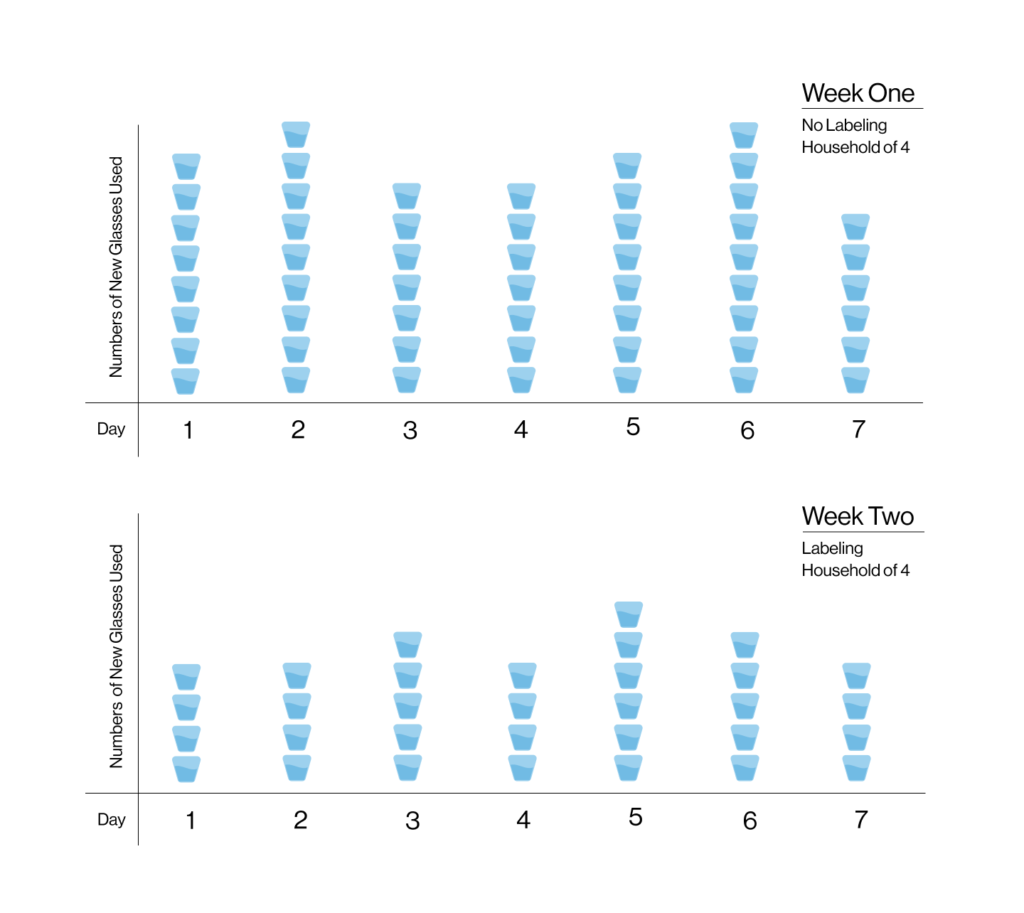

We observed that on a normal day, people used up to 2 to 3 glasses per person just for water. Sometimes they would forget which glass belonged to whom, and would grab a new glass from the shelf, adding to the already piling stack of used glasses.

Intervention

In order to “persuade” our family members to reduce the use of water glasses, we labelled the cups with the names of our family members. The idea behind being that people will only use the glass labeled with their name throughout the day.

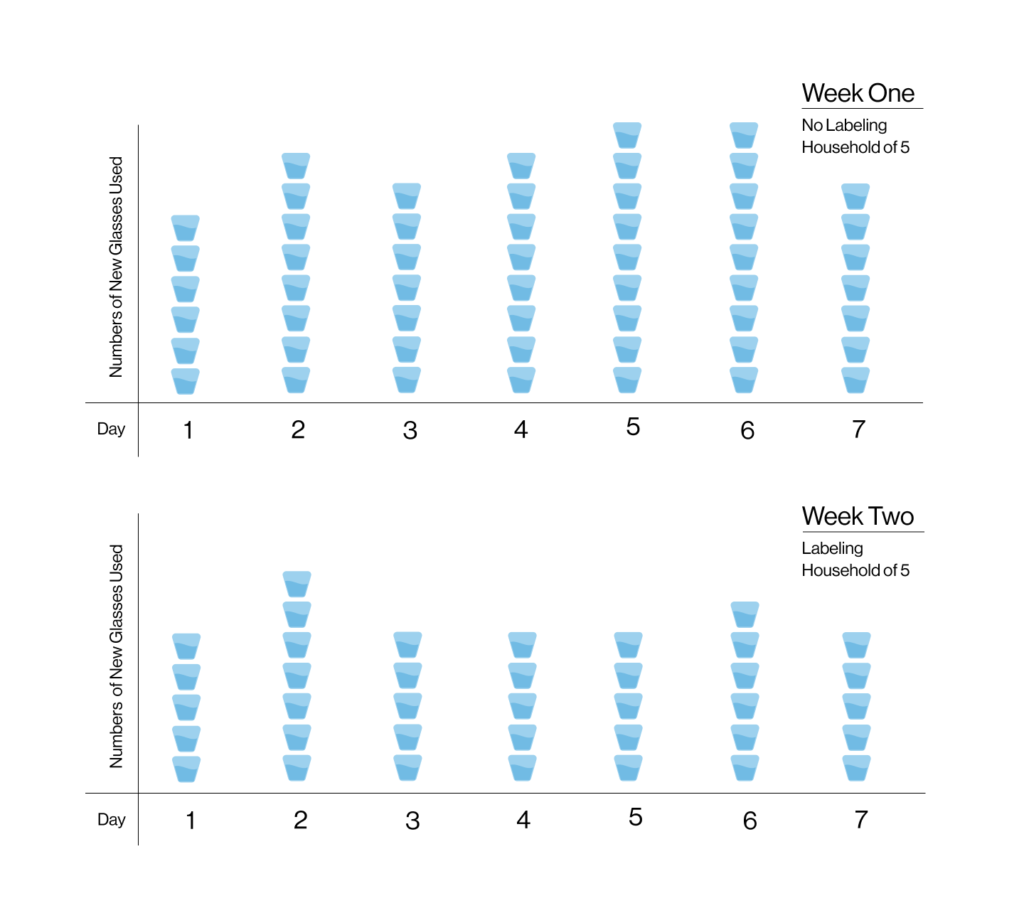

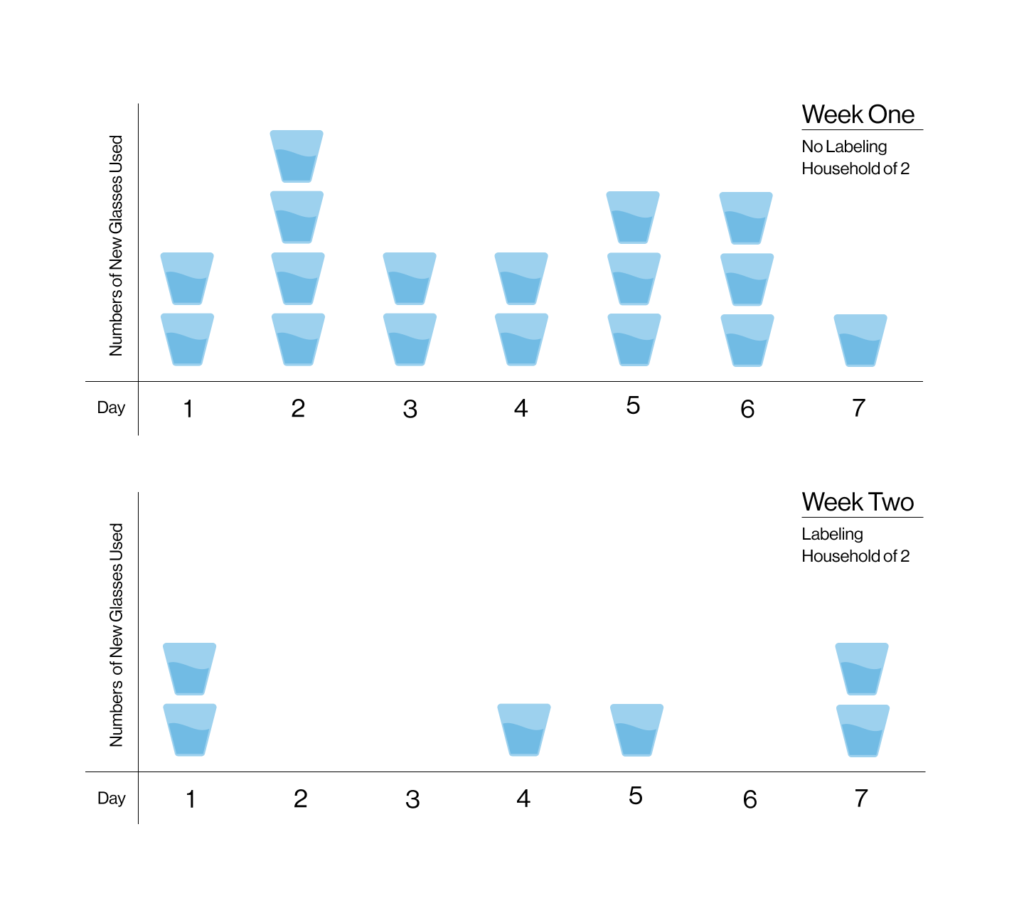

Results

Visualization

Eliza’s Experience

Occasionally people would use their labeled glasses for drinks other than water, prompting them to grab another unlabeled glass later in the day. There is a significant variety of glass shapes in Eliza’s house, which may have affected her housemate’s preferences.

Thomas

After labeling the glasses, the same glasses were used not just through one day, but for multiple days; sometimes as long as 3. The glasses were used repeatedly until there was a visible grease/fingerprint residue on the surface.

Margot

When the glasses were labeled the amount of new glasses used per day went down a good amount. People tended to reuse glasses with labels, but not always the ones with their name. This made everyone have to shift glasses around.

Reflection

The levels of effectiveness of this project varied by our respective living situations. One of the distinctive factors that affected our methods were elements of attachment and personalization. While Thomas and Margot’s households have uniform glasses, Eliza’s family has a collection of different shapes and sizes. When the labeling was not the only element of distinction, people’s affinity for certain glasses outweighed the personalization of having a labeled cup.

Since our persuasion method was not entirely subtle (people had to know something was up), we all initially benefited from the element of surprise and the novelty of the intervention. When we only have our living partners to test psychological experiments on, it can be harder to gage if the method alone is purely effective or if they are more responsive because we offer a brief disruption from the monotony of social isolation. In the case of Margot and Eliza, they had to change up their tactics mid-week to keep their families engaged with the behavioral shift.

Another distinctive influence on our project was how our families and housemates are affected by the coronavirus pandemic. As a result of quarantine, we are spending significantly longer periods of time in the house in close quarters. With lots on our minds, it’s easy to forget about little things like forgetting your water glass on the coffee table. Secondly, we are particularly concerned about physical health and preventing the spread of germs. Prior to the intervention, if you couldn’t remember which glass you left in the living room, it felt safer to simply grab a new glass than risk drinking out of someone else’s cup. Our persuasion method inadvertently helped prevent this fear and could give people peace of mind they weren’t aiding the spread of germs in close quarters.